Location

Please select your investor type by clicking on a box:

We are unable to market if your country is not listed.

You may only access the public pages of our website.

We believe there are three main levers of change: policy change, through multilateral agreements by countries, legal challenge through litigation, and corporate and community action. All ultimately seeking to impose a price on pollution.

In our view, companies are increasingly vulnerable to policy and litigation risks, some are opting to set internal carbon prices (ICPs) to better account for this. An ICP is a self-imposed pricing mechanism that companies use to quantify the cost of their carbon emissions, incentivizing reduction strategies and aligning their operations with broader sustainability goals.

On the face of it ICPs have the potential to be an effective tool in increasing corporate resilience and reducing emissions. Yet the operation and consequences of ICPs are poorly understood.

As a firm, we have partnered with the University of Exeter to research this important lever of corporate policy. Find out more about our partnership here.

The ‘tragedy of the commons’ occurs when the self-interest of individual actors leads to the failure of the entire system. Unlike Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ when self-interest is the motivation behind trade, exchange, and economic prosperity, self-interest has led to higher emissions and deteriorating climate quality. Short-term economic prosperity has been achieved at the expense of long-term economic, social, and environmental prosperity.

Economists argue that this has occurred because environmental public goods are not priced effectively. There is no disincentive to pollute because the profits of activity are private, but the losses of from increased emissions are shared globally. From a purely financial sense, therefore, considering pollution could even put a firm at a financial competitive disadvantage in the short term against those that continue to emit. Especially given we are seeing the marginal cost of abatement increase.

This is an example of market failure as the full costs associated with economic activity are not captured. The answer for solving this problem may seem obvious: simply price the externality so that economic decisions will take into account their full environmental cost. However, what sounds simple in theory is hard to achieve in practice. With a single common atmosphere, a single common price would be most relevant. But that will require international agreement on carbon budgets, price setting mechanisms, and a reckoning, most likely, on the past benefit of historic unpriced emissions. This is difficult to achieve in practice.

Yet the world is constrained by a carbon budget above which the system is threatened and ultimately compromised. The socioeconomic cost of this budget being exceeded is immense1. So, although finding international agreement is hard in practice, the threat of failure has provided the motivation for countries to come together to try and resolve a path forward.

The annual COP climate change summits provided the forum for this with the 2015 Paris meeting seeing countries agree on their own contributions and targets to reducing future emissions. This was an important step in keeping the world’s emissions within the carbon budget, but nearly a decade later, progress has been varied and a Paris aligned world seems to be an unattainable dream. The global pandemic demanded an immediate governmental response that, in some cases, has absorbed the headroom to invest in energy transitions. It also highlighted societal inequalities, some of which have led to changes in governments, not all of which are as supportive of the aims of the Paris Agreement. This has led to warnings that climate change progress isn’t fast enough and that government commitments will not be strong enough to achieve what is needed to mitigate climate risks – a sobering reality. Relying on governments’ pledges, however, is not the only route for environmental progress. There are two others.

The first is legal. In common law legal systems, we are beginning to witness the application of the duty of care principle to environmental pollution. This is analogous to the arguments made against tobacco firms in the 1970s and 1980s which were sued for the harm their products did to customers. The harm was initially direct, but eventually it was successfully argued that it was also indirect through ‘passive smoking’. Tobacco firms were obliged to settle vast sums in damages. In effect, the litigation established a cost on the externalities of smoking, forcing the industry to confront its past business practices and leading to a period of much tighter regulation and higher prices.

Such arguments are now being used again, only instead of passive smoking, the law is looking to attribution science. Linking the effect of changing weather and rising sea levels with anthropogenic forcing, high emitting companies are increasingly finding themselves as the defendant.

These are difficult arguments to make and are hard to prove. Not all courts think the same on such matters either, but courts have a way of filling legislative voids with case law and, as such, often reflect the debates within and the opinions of society through the types of cases the public wishes to bring.

As the economic, social and environmental costs of climate change become ever more pressing, and the public more concerned, we should expect environmental litigation to increase. The primary targets are likely to be the legacy oil & gas, and broader energy companies, where the link to climate change is more apparent. It is less likely that legal action will be brought against firms in other industries where emissions are lower or where there isn’t a strong direct connection between the business model and carbon intensive activities.

This then leaves scope for the second possible alternative route for managing climate emissions: unilateral action from governments and communities. We are already seeing this in the way in which cities are choosing to implement road charging schemes, for example, or individual countries are considering carbon border adjustment taxes. For investors, all of the above approaches for addressing climate change, be that multilateral action agreed across countries, legal challenges, or local communities unilaterally pursuing change, expose corporations to increasing policy and litigation risk.

The above mechanisms may vary but in essence, the objective is the same: to ensure that carbon externalities are priced. Without change, the effect on corporations could be considerable. We are beginning to see some corporates respond proactively by anticipating this change and implementing their own Internal Carbon Price (ICP) when assessing business performance and new projects.

An Internal Carbon Price (IPC) is a mechanism through which companies can place a monetary value on their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as a way of prioritising low-carbon projects. It provides visibility on climate risk and costs allowing companies to develop strategies and steer business decisions in a way that protects the longevity of the business.

Practically ICP often takes several forms:

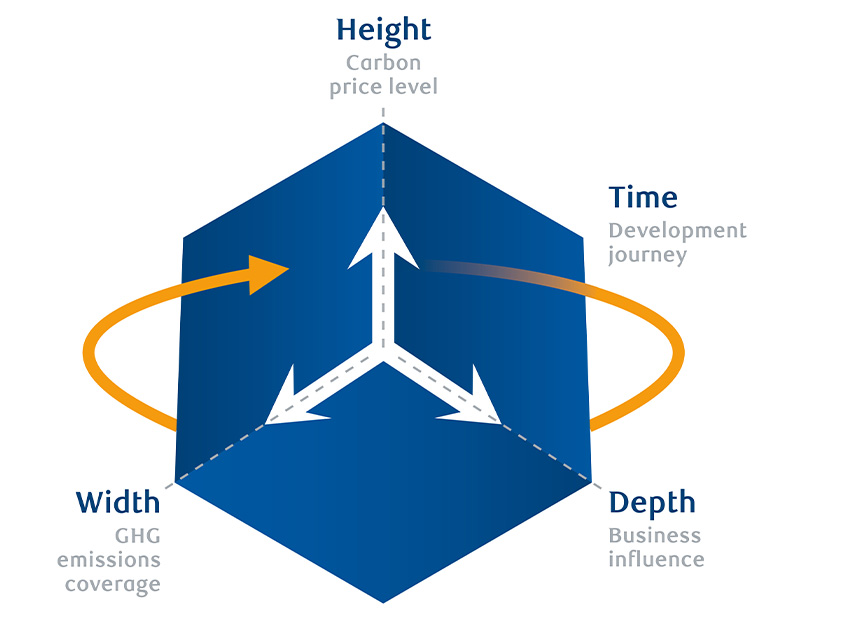

There are four main dimensions to any ICP; business influence, development journey, carbon price level, and GHG emission coverage.

The weight of each of these is heavily influenced by the macro impact of government policy, legal challenge, and community sentiment.

While ICPs are generally used to drive low-carbon investments, they also serve to drive energy efficiency gains, change internal behaviour, and stress test investments, as well as helping to navigate GHG regulations and stakeholder expectations.

Whilst the mechanisms of the internal carbon price are now well established, there is limited understanding of how this tool can be used most effectively.

Our sense is that the need for an effective climate transition is only becoming more pressing as time passes and the world’s carbon budget is fully utilised. The risks appear to be rising and for investors this is increasingly becoming something that is not just theoretical, but has the potential to influence the path of long-term profit expectations, such as considerations typically employed in discounted cash flows, which drive pricing in the market.

An Internal Carbon Price may thus be an important policy lever for firms to manage these risks and offer a signal to investors that their investments are more resilient to climate policy and litigation risks. This is why we have collaborated with the University of Exeter to research this area in more detail and why we now await the publication of that research with great interest.

Suscríbase ahora para recibir las últimas perspectivas económicas y de inversión de nuestros expertos directamente en su bandeja de correo.

Este documento es una comunicación de marketing y puede ser producido y emitido por las siguientes entidades: en el Espacio Económico Europeo (EEE), por BlueBay Funds Management Company S.A. (BBFM S.A.), sociedad regulada por la Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF). En Alemania, Italia, España y los Países Bajos, BBFM S. A opera con un pasaporte de sucursal con arreglo a lo dispuesto en la Directiva sobre organismos de inversión colectiva en valores mobiliarios (2009/65/CE) y la Directiva relativa a los gestores de fondos de inversión alternativos (2011/61/UE). En el Reino Unido por RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited (RBC GAM UK), sociedad autorizada y regulada por la Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) del Reino Unido, registrada ante la Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) de los Estados Unidos y miembro de la National Futures Association (NFA) autorizada por la Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) de los Estados Unidos. En Suiza, por BlueBay Asset Management AG, país en el que el Representante y Agente de pagos es BNP Paribas Securities Services, Paris, succursale de Zurich, Selnaustrasse 16, 8002 Zurich (Suiza). El lugar de ejecución es el domicilio social del Representante. Los órganos judiciales del domicilio social del representante suizo o el domicilio social o lugar de residencia del inversor tendrán la competencia para conocer las reclamaciones relacionadas con la oferta o publicidad de acciones en Suiza. El Folleto, los Documentos de datos fundamentales para el inversor (KIID), los documentos de datos fundamentales (KID) de los PRIIP (productos de inversión minorista vinculados y los productos de inversión basados en seguros), cuando proceda, la escritura de constitución y cualquier otro documento necesario, por ejemplo, los informes anuales y semestrales, pueden obtenerse de manera gratuita solicitándolos al Representante en Suiza. En Japón, por BlueBay Asset Management International Limited, sociedad registrada ante la Kanto Local Finance Bureau del Ministerio de Finanzas de Japón. En Asia, por RBC Global Asset Management (Asia) Limited, sociedad registrada ante la Comisión del Mercado de Valores y Futuros de Hong Kong. En Australia, RBC GAM UK se encuentra exenta del cumplimiento de la obligación de poseer una licencia de servicios financieros australiana en virtud de la Ley de sociedades (Corporations Act) para la prestación de servicios financieros, ya que está regulada por la FCA de acuerdo con la legislación del Reino Unido, que difiere de la australiana. En Canadá, por RBC Global Asset Management (incluido PH&N Institutional), sociedad regulada por cada una de las comisiones provinciales y territoriales del mercado de valores ante la que esté registrada. RBC GAM UK no se encuentra registrada en virtud de la legislación sobre valores negociables, sino que se acoge a la exención para operadores internacionales contemplada por la legislación provincial aplicable a esta materia, la cual permite a RBC GAM UK llevar a cabo determinadas actividades específicas como operador para los residentes canadienses que tengan la calificación de «cliente canadiense permitido» (Canadian permitted client), según la definición de dicho término en la legislación aplicable a valores negociables. En Estados Unidos, por RBC Global Asset Management (U.S.) Inc. («RBC GAM-US»), asesor de inversiones registrado ante la SEC. Las entidades señaladas anteriormente se denominan colectivamente «RBC BlueBay» en el presente documento. No debe interpretarse que las afiliaciones y los registros mencionados comportan un apoyo a RBC BlueBay ni tampoco su aprobación por parte de las respectivas autoridades competentes en materia de licencias o registros. No todos los productos, servicios e inversiones que se describen en el presente documento están disponibles en todas las jurisdicciones, y algunos de ellos solo lo están de forma limitada, debido a las exigencias jurídicas y normativas locales.

El documento va dirigido exclusivamente a «Clientes Profesionales» y «Contrapartes Elegibles» (como se define en la Directiva relativa a los mercados de instrumentos financieros [«MiFID»]); o en Suiza a los «Inversores Cualificados», tal y como se definen en el Artículo 10 de la Ley suiza de organismos de inversión colectiva y su ordenanza de aplicación; o en Estados Unidos a «Inversores Acreditados» (según la definición de la Ley de valores negociables [Securities Act] de 1933) o «Compradores Cualificados» (conforme a la definición de la Ley de sociedades de inversión [Investment Company Act] de 1940), según sea aplicable, y ninguna otra categoría de cliente debería basarse en él.

Salvo indicación en contrario, todos los datos proceden de RBC BlueBay. Según el leal saber y entender de RBC BlueBay, este documento es veraz y correcto en la fecha de su emisión. RBC BlueBay no otorga ninguna garantía ni realiza ninguna manifestación ni expresa ni tácita con respecto a la información incluida en este documento y excluye expresamente en este acto toda garantía de exactitud, integridad o adecuación a un fin concreto. Las opiniones y estimaciones están basadas en nuestro propio criterio y podrían cambiar sin previo aviso. RBC BlueBay no proporciona asesoramiento de inversión ni de ningún otro tipo. El contenido del presente documento no constituye asesoramiento alguno ni debe interpretarse como tal. El presente documento no constituye una oferta para vender, ni una solicitud de una oferta para comprar, ningún título o producto de inversión en ninguna jurisdicción. Esta información se ofrece únicamente a efectos informativos.

Queda prohibida toda reproducción, redistribución o transmisión directa o indirecta de este documento a cualquier otra persona, o su publicación, total o parcial, para cualquier fin y de cualquier modo, sin el previo consentimiento por escrito de RBC BlueBay. Copyright 2023 © RBC BlueBay. RBC Global Asset Management (RBC GAM) es la división de gestión de activos de Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) que incluye a RBC Global Asset Management (U.S.) Inc. (RBC GAMUS), RBC Global Asset Management Inc., RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited y RBC Global Asset Management (Asia) Limited, entidades mercantiles independientes, pero vinculadas. ® / Marca(s) registrada(s) de Royal Bank of Canada y BlueBay Asset Management (Services) Ltd. Utilizada(s) con autorización. BlueBay Funds Management Company S.A., con domicilio social en 4, Boulevard Royal L-2449 Luxemburgo, sociedad registrada en Luxemburgo con el número B88445. RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited, con domicilio social 100 Bishopsgate, London EC2N 4AA, sociedad registrada en Inglaterra y Gales con el número 03647343. Todos los derechos reservados

Suscríbase ahora para recibir las últimas perspectivas económicas y de inversión de nuestros expertos directamente en su bandeja de correo.