Location

Please select your investor type by clicking on a box:

We are unable to market if your country is not listed.

You may only access the public pages of our website.

We believe there are three main levers of change: policy change, through multilateral agreements by countries, legal challenge through litigation, and corporate and community action. All ultimately seeking to impose a price on pollution.

In our view, companies are increasingly vulnerable to policy and litigation risks, some are opting to set internal carbon prices (ICPs) to better account for this. An ICP is a self-imposed pricing mechanism that companies use to quantify the cost of their carbon emissions, incentivizing reduction strategies and aligning their operations with broader sustainability goals.

On the face of it ICPs have the potential to be an effective tool in increasing corporate resilience and reducing emissions. Yet the operation and consequences of ICPs are poorly understood.

As a firm, we have partnered with the University of Exeter to research this important lever of corporate policy. Find out more about our partnership here.

The ‘tragedy of the commons’ occurs when the self-interest of individual actors leads to the failure of the entire system. Unlike Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ when self-interest is the motivation behind trade, exchange, and economic prosperity, self-interest has led to higher emissions and deteriorating climate quality. Short-term economic prosperity has been achieved at the expense of long-term economic, social, and environmental prosperity.

Economists argue that this has occurred because environmental public goods are not priced effectively. There is no disincentive to pollute because the profits of activity are private, but the losses of from increased emissions are shared globally. From a purely financial sense, therefore, considering pollution could even put a firm at a financial competitive disadvantage in the short term against those that continue to emit. Especially given we are seeing the marginal cost of abatement increase.

This is an example of market failure as the full costs associated with economic activity are not captured. The answer for solving this problem may seem obvious: simply price the externality so that economic decisions will take into account their full environmental cost. However, what sounds simple in theory is hard to achieve in practice. With a single common atmosphere, a single common price would be most relevant. But that will require international agreement on carbon budgets, price setting mechanisms, and a reckoning, most likely, on the past benefit of historic unpriced emissions. This is difficult to achieve in practice.

Yet the world is constrained by a carbon budget above which the system is threatened and ultimately compromised. The socioeconomic cost of this budget being exceeded is immense1. So, although finding international agreement is hard in practice, the threat of failure has provided the motivation for countries to come together to try and resolve a path forward.

The annual COP climate change summits provided the forum for this with the 2015 Paris meeting seeing countries agree on their own contributions and targets to reducing future emissions. This was an important step in keeping the world’s emissions within the carbon budget, but nearly a decade later, progress has been varied and a Paris aligned world seems to be an unattainable dream. The global pandemic demanded an immediate governmental response that, in some cases, has absorbed the headroom to invest in energy transitions. It also highlighted societal inequalities, some of which have led to changes in governments, not all of which are as supportive of the aims of the Paris Agreement. This has led to warnings that climate change progress isn’t fast enough and that government commitments will not be strong enough to achieve what is needed to mitigate climate risks – a sobering reality. Relying on governments’ pledges, however, is not the only route for environmental progress. There are two others.

The first is legal. In common law legal systems, we are beginning to witness the application of the duty of care principle to environmental pollution. This is analogous to the arguments made against tobacco firms in the 1970s and 1980s which were sued for the harm their products did to customers. The harm was initially direct, but eventually it was successfully argued that it was also indirect through ‘passive smoking’. Tobacco firms were obliged to settle vast sums in damages. In effect, the litigation established a cost on the externalities of smoking, forcing the industry to confront its past business practices and leading to a period of much tighter regulation and higher prices.

Such arguments are now being used again, only instead of passive smoking, the law is looking to attribution science. Linking the effect of changing weather and rising sea levels with anthropogenic forcing, high emitting companies are increasingly finding themselves as the defendant.

These are difficult arguments to make and are hard to prove. Not all courts think the same on such matters either, but courts have a way of filling legislative voids with case law and, as such, often reflect the debates within and the opinions of society through the types of cases the public wishes to bring.

As the economic, social and environmental costs of climate change become ever more pressing, and the public more concerned, we should expect environmental litigation to increase. The primary targets are likely to be the legacy oil & gas, and broader energy companies, where the link to climate change is more apparent. It is less likely that legal action will be brought against firms in other industries where emissions are lower or where there isn’t a strong direct connection between the business model and carbon intensive activities.

This then leaves scope for the second possible alternative route for managing climate emissions: unilateral action from governments and communities. We are already seeing this in the way in which cities are choosing to implement road charging schemes, for example, or individual countries are considering carbon border adjustment taxes. For investors, all of the above approaches for addressing climate change, be that multilateral action agreed across countries, legal challenges, or local communities unilaterally pursuing change, expose corporations to increasing policy and litigation risk.

The above mechanisms may vary but in essence, the objective is the same: to ensure that carbon externalities are priced. Without change, the effect on corporations could be considerable. We are beginning to see some corporates respond proactively by anticipating this change and implementing their own Internal Carbon Price (ICP) when assessing business performance and new projects.

An Internal Carbon Price (IPC) is a mechanism through which companies can place a monetary value on their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as a way of prioritising low-carbon projects. It provides visibility on climate risk and costs allowing companies to develop strategies and steer business decisions in a way that protects the longevity of the business.

Practically ICP often takes several forms:

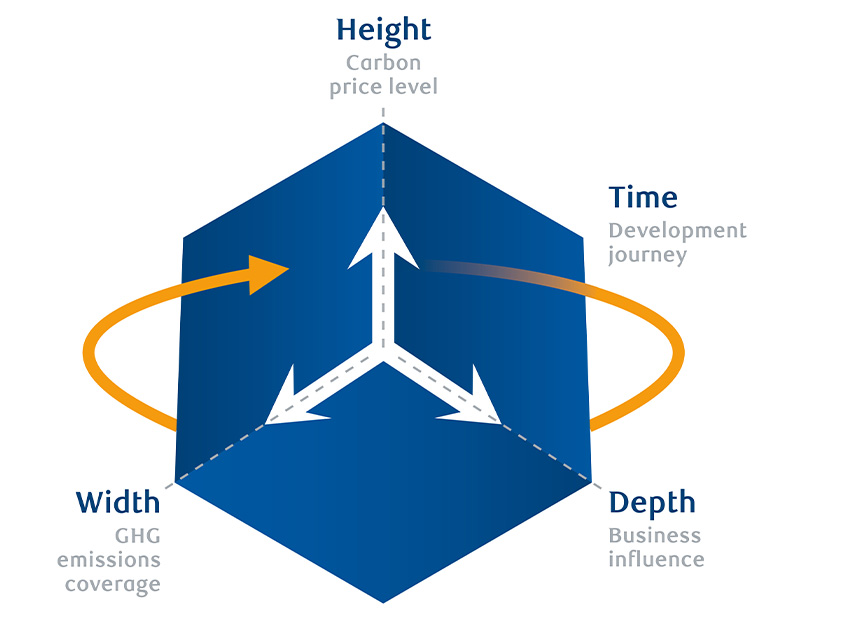

There are four main dimensions to any ICP; business influence, development journey, carbon price level, and GHG emission coverage.

The weight of each of these is heavily influenced by the macro impact of government policy, legal challenge, and community sentiment.

While ICPs are generally used to drive low-carbon investments, they also serve to drive energy efficiency gains, change internal behaviour, and stress test investments, as well as helping to navigate GHG regulations and stakeholder expectations.

Whilst the mechanisms of the internal carbon price are now well established, there is limited understanding of how this tool can be used most effectively.

Our sense is that the need for an effective climate transition is only becoming more pressing as time passes and the world’s carbon budget is fully utilised. The risks appear to be rising and for investors this is increasingly becoming something that is not just theoretical, but has the potential to influence the path of long-term profit expectations, such as considerations typically employed in discounted cash flows, which drive pricing in the market.

An Internal Carbon Price may thus be an important policy lever for firms to manage these risks and offer a signal to investors that their investments are more resilient to climate policy and litigation risks. This is why we have collaborated with the University of Exeter to research this area in more detail and why we now await the publication of that research with great interest.

Iscriviti ora per ricevere gli ultimi approfondimenti economici e sugli investimenti dei nostri esperti, inviati direttamente alla tua casella di posta elettronica.

Il presente documento costituisce una comunicazione di marketing e può essere prodotto e distribuito dai soggetti di seguito specificati. Nello Spazio Economico Europeo (SEE) il soggetto autorizzato è BlueBay Funds Management Company S.A. (BBFM S.A.), che è regolamentata dalla Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF). In Germania, Italia, Spagna e Paesi Bassi, BFM S.A. opera con un passaporto di filiale ai sensi della Direttiva sugli Organismi di investimento collettivo in valori mobiliari (2009/65/CE) e della Direttiva sui Gestori di Fondi di investimento alternativo (2011/61/UE). Nel Regno Unito, la produzione e distribuzione sono curate da RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited (RBC GAM UK), che è autorizzata e regolamentata dall’Autorità di vigilanza finanziaria del Regno Unito (FCA), registrata presso la Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) statunitense e membro della National Futures Association (NFA) su autorizzazione della Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) statunitense. In Svizzera, la produzione e distribuzione sono curate da BlueBay Asset Management AG il cui Rappresentante e agente per i pagamenti è BNP Paribas Securities Services, Paris, succursale de Zurich, Selnaustrasse 16, 8002 Zurigo (Svizzera). Il luogo di adempimento è stabilito presso la sede legale del Rappresentante. I tribunali della sede legale del rappresentante svizzero o della sede legale o del luogo di residenza dell’investitore sono competenti per i reclami relativi all’offerta e/o alla pubblicità di azioni in Svizzera. Il Prospetto, i Documenti contenenti le informazioni chiave per gli investitori (KIID), i Documenti contenenti le informazioni chiave dei Prodotti d’investimento al dettaglio e assicurativi preassemblati (KID dei PRIIP), ove applicabili, lo Statuto e qualsiasi altro documento richiesto, come le Relazioni annuali e infrannuali, si possono ottenere gratuitamente dal Rappresentante in Svizzera. In Giappone, la produzione e distribuzione sono curate da BlueBay Asset Management International Limited, che è registrata presso il Kanto Local Finance Bureau del Ministero delle Finanze giapponese. In Asia, la produzione e distribuzione sono curate da RBC Global Asset Management (Asia) Limited, società registrata presso la Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) di Hong Kong. In Australia, RBC GAM UK è esente dall’obbligo di possedere una licenza australiana di servizi finanziari ai sensi del Corporations Act per quanto riguarda i servizi finanziari, in quanto è regolata dalla FCA secondo le leggi del Regno Unito che differiscono dalle leggi australiane. In Canada, da RBC Global Asset Management Inc. (che include PH&N Institutional), che è regolamentata dalle commissioni titoli provinciali e territoriali presso la quale è registrata. RBC GAM UK non è registrata ai sensi delle leggi sui valori mobiliari e si affida all'esenzione per i dealer internazionali prevista dalla legislazione provinciale applicabile sui valori mobiliari, che consente a RBC GAM UK di svolgere alcune attività specifiche di dealer per quei residenti canadesi che si qualificano come "cliente canadese autorizzato", in quanto tale termine è definito dalla legislazione applicabile sui valori mobiliari. Negli Stati Uniti, la produzione e distribuzione sono curate da RBC Global Asset Management (U.S.) Inc. (“RBC GAM-US”), una società di consulenza finanziaria registrata presso la SEC. Le entità di cui sopra sono collettivamente denominate “RBC BlueBay” all’interno del presente documento. Le registrazioni e adesioni effettuate non devono intendersi quale approvazione o autorizzazione di RBC BlueBay da parte delle rispettive autorità preposte al rilascio delle licenze o alla registrazione. I prodotti, i servizi o gli investimenti qui descritti possono non essere disponibili in tutte le giurisdizioni o essere disponibili solo su base limitata, a causa dei requisiti normativi e legali locali.

Il presente documento è destinato esclusivamente a “Clienti professionali” e “Controparti qualificate” (come definite dalla Direttiva sui mercati degli strumenti finanziari (“MiFID”) o dalla FCA); in Svizzera a “Investitori qualificati”, come definiti dall’Articolo 10 della Legge svizzera sugli investimenti collettivi di capitale e della relativa ordinanza attuativa; negli Stati Uniti, a “Investitori accreditati” (come definiti nel Securities Act del 1933) o ad “Acquirenti qualificati” (come definiti nell’Investment Company Act del 1940), a seconda dei casi, e non dev’essere considerato attendibile da altra categoria di clienti.

Se non diversamente specificato, tutti i dati sono stati forniti da RBC BlueBay. Per quanto a conoscenza di RBC BlueBay, il presente documento è veritiero e corretto alla data attuale. RBC BlueBay non rilascia alcuna garanzia esplicita o implicita né alcuna dichiarazione riguardo alle informazioni contenute nel presente documento e declina espressamente ogni garanzia di accuratezza, completezza o idoneità per un particolare scopo. Opinioni e stime derivano da una nostra valutazione e sono soggette a modifica senza preavviso. RBC BlueBay non fornisce consulenza in materia di investimenti né di altra natura e il presente documento non esprime alcuna consulenza né deve essere interpretato come tale. Il presente documento non costituisce un’offerta di vendita o la sollecitazione di un’offerta di acquisto di titoli o prodotti d’investimento in qualsiasi giurisdizione e ha finalità puramente informative.

È fatto divieto di riprodurre, distribuire o trasmettere, direttamente o indirettamente, ogni parte del presente documento a qualsiasi altra persona o di pubblicare, in tutto o in parte, i suoi contenuti per qualunque scopo e in qualsiasi modo senza il previo consenso scritto di RBC BlueBay. Copyright 2023 © RBC BlueBay. RBC Global Asset Management (RBC GAM) è la divisione di gestione patrimoniale di Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) che comprende RBC Global Asset Management Inc. (U.S.) Inc. (RBC GAMUS), RBC Global Asset Management Inc., RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited e RBC Global Asset Management (Asia) Limited, società indipendenti ma affiliate di RBC. ® / Marchio/i registrato/i di Royal Bank of Canada e BlueBay Asset Management (Services) Ltd. Utilizzato su licenza. BlueBay Funds Management Company S.A., sede legale all’indirizzo 4, Boulevard Royal L-2449 Luxembourg, società registrata in Lussemburgo con il numero B88445. RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited, con sede legale all’indirizzo 100 Bishopsgate, London EC2N 4AA, società in nome collettivo registrata in Inghilterra e Galles con il numero 03647343. Tutti i diritti riservati.

Iscriviti ora per ricevere gli ultimi approfondimenti economici e sugli investimenti dei nostri esperti, inviati direttamente alla tua casella di posta elettronica.