Location

Please select your investor type by clicking on a box:

We are unable to market if your country is not listed.

You may only access the public pages of our website.

Key takeaways

More than fifteen years on from the global financial crisis, European financial credit remains deeply out of favour – still overshadowed, arguably, by the legacy of an era most investors would rather forget. Yet the sector’s fundamentals have been transformed. Today, Europe’s banks are well-capitalised, increasingly profitable and far removed from the fragilities of the past. A gap has emerged between perception and pricing – and, for active investors, that misalignment presents opportunity.

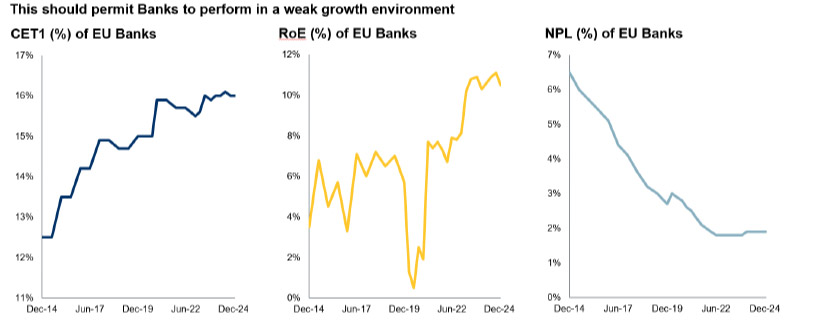

By most conventional measures, European banks are in robust health. As the chart below shows, core equity capital (CET1) across the sector now stands above 16% – a level that provides a meaningful cushion against both macroeconomic shocks and individual credit events. Profitability has also improved significantly, with the return on equity for European banks now exceeding 10% – higher than their US counterparts for the first time in many years. That recovery has been underpinned by improving net interest margins and a more disciplined approach to lending and balance sheet management.

Perhaps most notably, non-performing loan (NPL) ratios have declined to around 2%, a clear sign of improved asset quality across the sector. While the macro backdrop has become more uncertain in recent months, the banking system looks well equipped to cope with a weaker growth environment – with strong capital, improved earnings and cleaner loan books forming a more resilient base than at any point in recent memory.

Source: EBA, as at 31 December 2024.

Today’s European banks exhibit far more stable, almost utility-like characteristics than the under-capitalised and less-disciplined lenders whose weaknesses were exposed during the financial crisis. Yet despite this progress, valuations have been slow to catch up. In equity markets, the sector still trades on a price-to-earnings ratio close to its all-time lows – a sign that, even after years of reform, legacy perceptions continue to cast a long shadow.

That scepticism is also reflected in bond markets, where many European bank-issued instruments offer yields that seem totally disconnected from the underlying credit quality. Investors are effectively being rewarded with a significant premium to take on exposure to what are, in many cases, investment grade names with robust fundamentals.

However, for bonds, the disconnect isn’t just caused by sentiment. It is deepened by structural inefficiencies, the roots of which can be traced back to the financial crisis itself. In its aftermath, regulators overhauled the capital structures of European banks, introducing new instruments – such as additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds and contingent convertibles (CoCos) – to provide greater loss absorption and reduce taxpayer exposure in the event of failure. These instruments now account for a significant share of outstanding bank debt and they are typically issued by large, well-capitalised institutions with strong regulatory oversight.

Yet, despite their obvious quality characteristics, many of these securities are excluded from mainstream bond indices. Their hybrid structure and contractual features – such as call schedules or loss absorption triggers – though designed for regulatory robustness, place them outside index parameters. That exclusion has a material impact. It means these bonds are bypassed by passive investment strategies, which now account for a substantial and growing share of global fixed income flows.

The result is a structural market inefficiency. Fundamentally sound bonds – often from national champion banks – can trade at a discount simply because they sit outside the reach of index-driven demand.

The opportunity this creates is striking. Portfolios that target this part of the market can combine solid investment grade credit quality with income returns more commonly associated with high yield.

That kind of profile – strong credit fundamentals paired with such an appealing yield – is rare in global bond markets and difficult to replicate elsewhere without taking on additional risk.

While this structural mispricing persists, this part of the European financial credit market looks unusually well placed to deliver attractive risk-adjusted returns – especially for active investors with the flexibility to capture inefficiencies that benchmark-constrained strategies cannot.

At a time when many markets look fully valued, European financial credit stands out – not just for its improving fundamentals, but for an enduring structural tailwind that remains firmly in place. For investors willing to look beyond the benchmarks, it’s a part of the market that continues to offer compelling potential – but it takes specialist expertise to harness it.